Digestion is the process of breaking down food. Our bodies produce enzymes that are essential to digestion, but many people could benefit from extra support.

Helps Break Down Most Foods

The broad-spectrum formula includes helpful enzymes that can support the digestion of proteins, starches, sugars, lactose, fats, nuts, plant and fungi fibers, and gluten. Digestive Enzymes provides 18 different enzymes, some of which act together, and each is matched specifically to a certain kind of food. The formula can’t prevent food allergies or intolerances, but it can support healthy digestion in healthy people.

Get More From What You Eat

Chewing breaks up big bits of food, the stomach makes the pieces microscopic, and enzymes help to break apart those microscopic particles so they can be absorbed into the bloodstream. Some foods are hard to digest, and supplementary enzymes taken alongside those can help break them down for more efficient absorption. This could be useful to anyone who is looking to get the most from their food, including people on restricted diets, bodybuilders and the health-conscious.

Introduction

Digestion is an intricate and vital process that occurs in the human body every time we consume food. It transforms the food we eat into essential nutrients and energy that our body can utilize for various functions. This article will delve deep into the remarkable journey of how our food is digested and broken down in the stomach, small intestine, and large intestine, with the assistance of digestive enzymes and beneficial bacteria.

I. The Mouth: Where Digestion Begins

The digestive process initiates in the mouth, where the mechanical and chemical breakdown of food begins. As we chew our food, the teeth mechanically break it into smaller pieces, increasing the surface area for enzymes to act upon. Meanwhile, the salivary glands secrete saliva, which contains an enzyme called amylase.

1. Salivary Amylase: The First Enzymatic Step

Amylase primarily targets carbohydrates, breaking down complex starches into simpler sugars like maltose. This initial enzymatic action begins the process of carbohydrate digestion even before the food enters the stomach.

II. The Stomach: Mixing, Churning, and Acidic Digestion

The food, now in a semi-liquid state called chyme, travels from the mouth to the stomach through the esophagus. The stomach is a muscular organ with a highly acidic environment. Here, several important digestive processes take place:

1. Hydrochloric Acid (HCl): The Gastric Acid

The stomach lining secretes hydrochloric acid, creating an acidic environment with a pH of about 2. This acidic medium serves multiple purposes:

Activation of pepsinogen to pepsin, an enzyme that breaks down proteins.

Destruction of harmful bacteria and pathogens in ingested food.

Unfolding and breaking down proteins into smaller peptides.

2. Pepsin: The Protein-Digesting Enzyme

Pepsin, activated by the low pH, plays a central role in breaking down proteins into peptides. These smaller protein fragments are essential for further digestion in the small intestine.

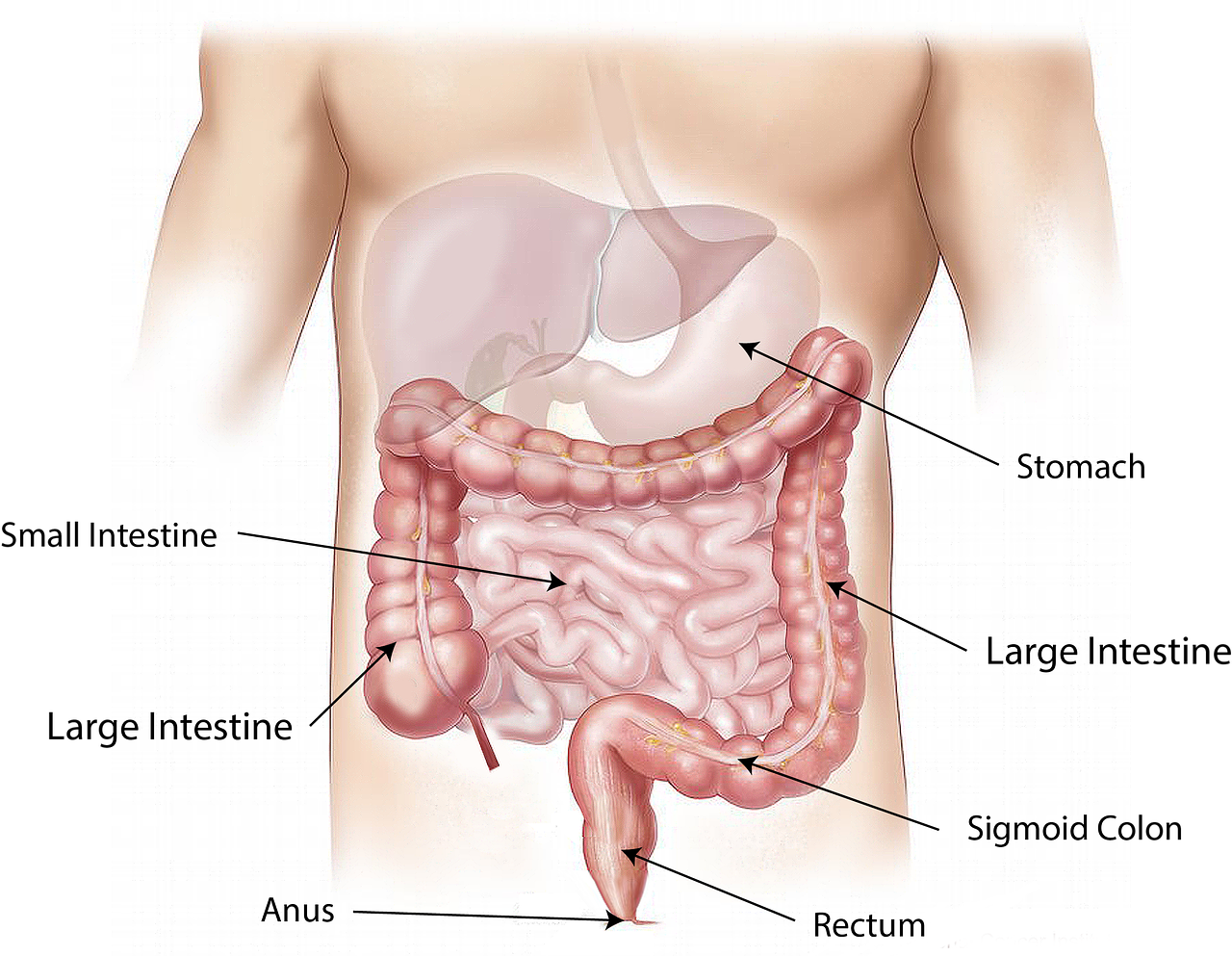

III. The Small Intestine: Absorption Central

The small intestine, a lengthy tube that stretches up to 20 feet, is where the majority of digestion and nutrient absorption occurs. It consists of three segments: the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum.

1. The Pancreatic Contribution

The pancreas is a crucial digestive organ located behind the stomach. It secretes digestive juices into the duodenum, containing enzymes that further break down food:

Pancreatic Amylase: Continues the breakdown of carbohydrates.

Pancreatic Lipase: Focuses on digesting dietary fats into fatty acids and glycerol.

Trypsin and Chymotrypsin: Protein-digesting enzymes that further cleave peptides into smaller fragments.

2. Bile: The Liver’s Gift

The liver produces bile, which is stored in the gallbladder and released into the duodenum when needed. Bile doesn’t contain enzymes but is essential for the digestion and absorption of fats. It emulsifies large fat globules, breaking them into smaller droplets, allowing lipase enzymes to work more efficiently.

3. Villi and Microvilli: The Absorption Superhighway

The walls of the small intestine are lined with millions of tiny finger-like projections called villi, which are covered with even smaller hair-like structures called microvilli. Together, they create an extensive surface area for nutrient absorption. As the partially digested food passes through the small intestine, nutrients are absorbed into the bloodstream through these villi and microvilli.

Carbohydrate Absorption: Simple sugars like glucose and fructose are absorbed directly into the bloodstream.

Protein Absorption: Peptides are broken down into amino acids and absorbed into the bloodstream.

Fat Absorption: Fatty acids and glycerol are absorbed into the lymphatic system before entering the bloodstream.

IV. The Large Intestine: Home to Beneficial Bacteria

The undigested and unabsorbed remnants of food reach the large intestine, the final stop in the digestive journey. While there’s no further enzymatic digestion of nutrients in this region, the large intestine plays a critical role in water absorption and houses a vast population of beneficial bacteria known as the gut microbiota.

1. Gut Microbiota: The Helpful Microorganisms

These bacteria assist in the fermentation of undigested carbohydrates and fibers, producing gases and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). SCFAs serve as an energy source for the colon cells and play a role in overall gut health.

2. Water Reabsorption: The Final Step

The large intestine absorbs most of the remaining water from the indigestible material, converting the semi-liquid chyme into a more solid form. This prepares the waste for elimination.

V. Elimination: Farewell to Waste

The remaining waste, now called feces, is stored in the rectum until it is ready to be eliminated through the anus. This process, known as defecation, is the final step in the digestive process.

Conclusion: The Incredible Journey of Digestion

The journey of food through the digestive system is an extraordinary process, involving the coordination of various organs, enzymes, and beneficial bacteria. From the initial breakdown of food in the mouth to the absorption of essential nutrients in the small intestine, and finally, the fermentation of undigested material in the large intestine, our body efficiently transforms the food we consume into the energy and nutrients necessary for our survival and well-being. Understanding this intricate process underscores the importance of a balanced and nutritious diet to support the body’s digestive functions and overall health.

When your body is not getting enough digestive enzymes to properly break down food, it may exhibit several signs and symptoms indicating digestive issues. These signs can vary in severity, and experiencing one or more of them does not necessarily mean you have a severe enzyme deficiency. However, they may suggest that your digestive system is not functioning optimally. Here are some common signs:

-

Bloating: If you frequently experience abdominal bloating after meals, it could be a sign of inadequate enzyme production. Undigested food in the digestive tract can lead to gas accumulation and discomfort.

-

Gas: Increased gas production, including belching and flatulence, can result from poor digestion. When food doesn’t break down properly, it can ferment in the gut, leading to gas formation.

-

Indigestion: Persistent indigestion, characterized by discomfort or a feeling of fullness during or after eating, may be related to enzyme insufficiency.

-

Diarrhea: In some cases, insufficient digestive enzymes can lead to diarrhea because undigested food can draw excess water into the intestines.

-

Constipation: Conversely, enzyme deficiencies can also result in constipation, as poorly digested food may move slowly through the digestive tract.

-

Foul-Smelling Stools: Stools that have an unusually strong or foul odor can be a sign of incomplete digestion.

-

Undigested Food in Stools: If you notice identifiable pieces of undigested food in your stools, it suggests that your body is not breaking down certain nutrients properly.

-

Abdominal Pain: Some individuals with enzyme deficiencies may experience abdominal pain, cramps, or discomfort as a result of improper digestion.

-

Nutrient Deficiencies: Over time, chronic enzyme insufficiency can lead to nutrient deficiencies because the body may not absorb essential vitamins and minerals effectively. This can manifest as symptoms such as fatigue, weakness, or brittle nails.

-

Weight Loss or Poor Weight Gain: In severe cases, chronic enzyme deficiencies can lead to unintended weight loss or poor weight gain, especially in children.

It’s important to note that these symptoms can overlap with various gastrointestinal conditions, and they don’t necessarily point solely to enzyme deficiencies. If you suspect you have digestive issues related to enzyme insufficiency, it’s advisable to consult a healthcare professional for a proper diagnosis and guidance on managing your digestive health. Additionally, they can recommend appropriate tests and interventions, which may include dietary changes or enzyme supplements if necessary.